Shaming is limiting. Period.

Stigma surrounding menstruation affects self-image, education.

December 10, 2015

When an activist posted a picture of herself wearing period-stained pants, Instagram censored it. When female politicians run for office, their capabilities are doubted due to hormone fluctuations. When female athletes mention menstruation, they are criticized and ridiculed.

Stigma and shame associated with menstruation influences female perception of self and limits a woman’s credibility and interaction within a community.

“Often times, especially in Western society, girls are ashamed of puberty because it represents this big change physically,” former Women’s Studies teacher Sarah Garlinghouse said. “So, your period as well as development of breasts is an actual physical reminder that you are changing — not only your role in society, but also everything about you. It’s a bridge from childhood to adulthood — that’s scary.”

Despite being a natural process, menstruation has become taboo, even holding unflattering euphemisms like “Aunt Flow” or “the crimson wave.”

“I think anywhere from ads on TV where they use the blue liquid instead of red normalize that periods aren’t supposed to be talked about,” senior Co-President of Femme Alliance Club Stella Smith-Werner said. “You’re not even supposed to show the blood.”

Menstruating women are often portrayed in advertisements as emotional wrecks or irrational and dependent non-functional members of society. Products show similar depictions. The recent MyPeriod Tracker app was created by five men who “were tired of the drama, discourse and sometimes absurd fights.”

“Inherent misogyny in a patriarchal world deems periods as dirty,” Garlinghouse said. “Women have often times in different religious texts have been called dirty or submale, from Adam’s rib. Men don’t have periods, so what better way to highlight a hierarchy than to ostracize those who are having a very normal bodily function.”

This holds true in politics evidenced by “Time” magazine’s opinion piece on Hillary Clinton and her better fit for presidency due to her postmenopausal state and through Donald Trump’s statement that debate moderator Megyn Kelly had “blood coming out of her eyes, blood coming out of her wherever” while asking him “all sorts of ridiculous questions.”

“I think in media there’s always a joke in the sense that women are inadequate while they are going through it,” Smith-Werner said.

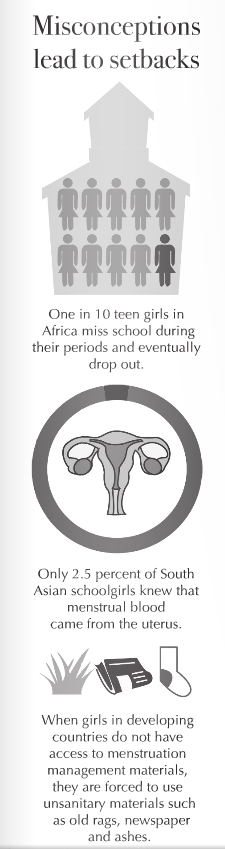

Period stigma extends to education in developing countries, where girls miss over 20 percent of their school year due to forced absences attributed to menstruation, according to a 2012 UNICEF survey.

“During my trip to the World Cup in South Africa, I met this young girl on a weekday, and I asked her, ‘Why aren’t you in school,’” Miki Agrawal, CEO of Thinx, a company committed to providing period-proof panties and breaking the menstruation taboo, said in her TedX Talk. “She said, ‘It’s my week of shame,’ and very embarrassedly told me that when she has her period, she misses a week of school. She tried using old rags but every time she went to go write on the chalkboard, the bits of rags would fall out, and the boys would laugh at her, and she’d run home crying.”

Contemporary perceptions of females and their bodies as toxic during periods can lead to ostracization from communities in developing countries, restricting worship and contact to people and livestock. Some women, such as those in Nepal, are even sent to isolated dwellings where they face danger from malnutrition, rape and animal predators, according to Femme International.

“To my horror, I found out that girls were using unimaginable things like sticks, leaves, mud, rags and plastic bags,” Agrawal said about her research on how girls in developing countries handled their periods. “Sixty-seven million girls in Africa alone start by missing one week of school every month and eventually ended up dropping out because of something as natural as their periods?”

Factoring in a lack of reproductive education, women are susceptible not only to infection but also unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, according to Plan International. A UN study shows that 48 percent of girls in Iran and 10 percent of girls in India believe menstruation is a disease.

“Menstruation management is a root cause for cyclical poverty in the developing world,” Agrawal said. “And, women are the greatest resource to elevating communities out of extreme poverty.”

Agrawal addressed the Girl Effect, a study which indicates that given an education, females will return $90 of $100 back to a community while males will only return $20 to $30. When girls drop out of school and get pregnant early, they aren’t productive members of society and can’t earn a living, equating to billions of dollars of lost income potential.

Agrawal and her company, which funds seven AFRIpads, sanitary pads created by Ugandan women, for every one Thinx underwear sold, saw an increase in graduation and pregnancy age rates when pads were made more accessible.

“When people are uncomfortable with issues, they don’t talk about it and change doesn’t happen,” Agrawal said. “Our mission expanded beyond just providing products and solutions for women here and there. Our mission became to break the taboo around this important issue that’s also so natural. We can create life. It’s beautiful, and it should not be called the week of shame.”

Garlinghouse says the best way to normalize something is to have open communication and not attach any shame, adding that a lot of boys are grossly uninformed about the female anatomy.

“There’s still people that hid their tampons up their sleeve when they go the bathroom and don’t like talking about it, but I see it more as an opportunity for girls to bond over as the struggle of being female,” Smith-Werner said. “ It’s a natural process that lasts seven days out of the month max. Women are really strong, and we know how to push past it.”