Zoë Newcomb

& Sara Kloepfer

Peering through the broken glass of the double doors in her backyard, Charlotte Svenson saw for the first time the insides of her childhood home destroyed. Svenson’s mother broke down sobbing in her daughter’s arms.

“My neighborhood showed no signs of civilization or the memories I cherished as a child,” Svenson, who at the time was an eighth grader at Academy of the Sacred Heart, New Orleans, said.

Once upon a time, Katrina was just a baby name. Now people know of it as the Category 5 monster that ripped apart the Louisiana coastline, killing more than 1500 and displacing countless other residents.

“I remember during our evacuation, before Katrina hit, going to bed when the hurricane was a Category 3, and then waking up to it being a Category 5 the next morning,” Meredith Schiro, then a sophomore, said. “That entire time period seems like a blur now.”

Remembering

Published five years ago today, The Broadview told the story of the aftermath of the storm and its effects on the lives of Sacred Heart students. Now the students reflect on what has changed since that unforgettable catastrophe. Students at the Academy of the Sacred Heart located in the Garden District of New Orleans were forced to transfer to schools around the country to continue their education. Most girls found a new home in Network schools, such as Academy of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau, La. and Duchesne Academy in Houston.

“My transition was relatively easy,” Clesi Bennet, who was a freshman when Katrina struck, said. “Our administration worked diligently to make everything as normal as possible. Although we weren’t in classrooms, ate lunch at Subway and didn’t always have chairs and tables, it was an experience I’ll never forget.”

Schiro remembers attending class in “the shack” — an old physical therapy building located on a service road on the side of the interstate. The girls gathered in the chapel to sing and pray for loved ones. Others found their transition more difficult.

“I was forced to merge with an entire new group of girls, in an entirely different city complete with a different culture and even different food,” Svenson said. “But Duchesne was a place I could get my mind off of things and pretend to be normal. As I entered high school, I began anew and left the memories and tragedies behind.”

Charlotte’s older sister Bridget, then a junior, felt similarly distanced from the realities that many residents who stayed behind faced.

“I didn’t watch the news and my mom didn’t tell us much about what was going on, so I don’t really have any bad Katrina memories,” Bridget Svenson said.

Some students were not so fortunate to be sheltered from the horrors of post-Katrina New Orleans.

“Everything just seemed to be in a military state,” Schiro said. “My family and I had to go pick up our MRE’s — military issued food. The entire city had this cloud of gloom and depression hovering over it. The water marks and wind-damaged structures were the wounds and scars left behind by Katrina.”

Bennett described being surrounded by knocked down structures, uprooted trees and lawns littered with debris, even refrigerators.

“I’ve never seen the city like that,” Bennett said. “But it was also amazing and so uplifting to see the numerous ‘WE’RE BACK’ or ‘WE WILL BE BACK SOON’ signs. It gave me hope to see people out in the streets cleaning and helping out their neighbors.

A ‘New Normal’

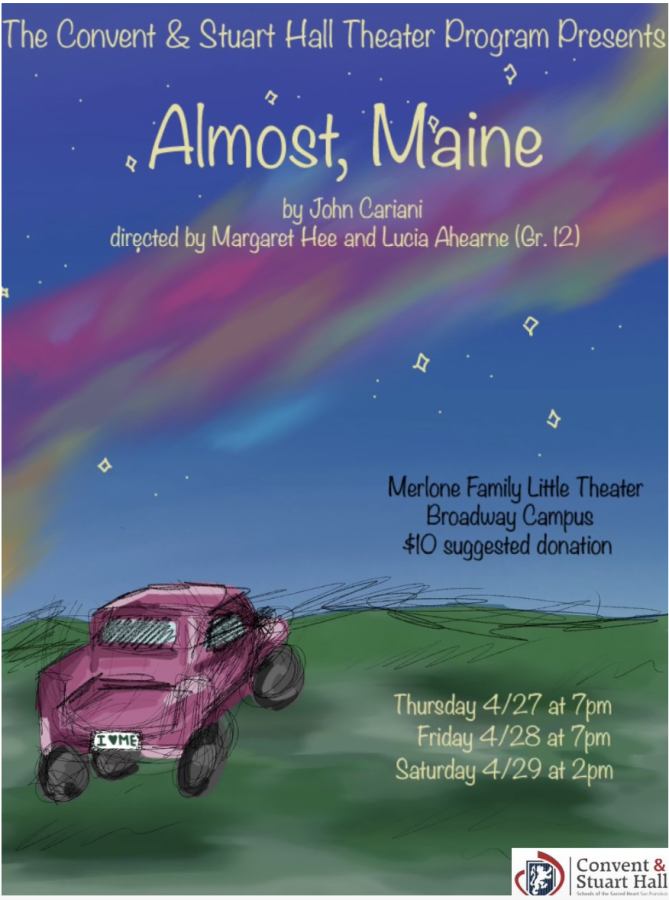

Even strangers came out to aid New Orleans, including Sacred Heart students. Convent and Stuart Hall students plan to return for the fourth annual community service trip this Thanksgiving. Students typically spend about five days restoring homes, gardening and visiting with residents.

“The girls [at Rosary] were really grateful,” CSH senior Frankie Incerty said. “Everyone was affected. Everyone either knew someone who lost their home, or their house was flooded or they had to transfer schools — everyone. One girl had to go all the way to Texas and didn’t talk to her family for two weeks.”

Five years ago, Charlotte Svenson voiced her regret for not appreciating the little things that make New Orleans special while she still had the time, saying “[the city] will never be the same.” However, the cultural vitality that characterizes New Orleans was not washed away in the flood.

“The city has found itself a new normal,” Schiro said. “Things are not quite exactly how they were before, but I feel like we have healed in our own way. We have not forgotten, but life moves on and it’s the only thing we can really do.”

The city’s sense of pride has returned in full force, residents say.

“If you thought people were passionate about New Orleans before, well, you should see them now,” Bennett said. “New Orleanians are obsessed with city, the Saints, the food, the music, the culture — everything.”

The Saints, once considered among the worst in the NFL, even referred to as the “Ain’ts,” bounced back to win the Super Bowl last year. The team’s ability to overcome their opponents on the field symbolized the city’s rebirth after Katrina.

‘Mess to Clean Up’

While New Orleans is still celebrating its unique culture, the city still has a mess to clean up. Incerty described going on a “reality tour” of the Lower 9th Ward where the levees broke. The neighborhood looked like it had been hit only a month ago. Rotting houses are washed bare except for bold X’s and numbers painted over the doorways, showing how many people had died inside.

“It was eye-opening because we didn’t see any of that on the news,” Incerty said.

There is a large discrepancy between the areas of the city that have been restored, like the uptown area where the Sacred Heart school is, versus the still-devastated projects of the 9th Ward.

“We got three different perspectives from the Sacred Heart girls – one was not affected at all, one was somewhat affected, and one had lost everything,” said Green. “They were still angry five years later, even the one who hadn’t lost everything. They were pissed at the government for not doing anything in all that time following the hurricane.”

Although Louisiana’s Road Home program provided nearly $8.6 billion in aid to rebuild homes, it is winding down, leaving property owners who have not tapped these funds no longer eligible for help. Their only hope may be the community groups volunteering to restore the city, such as Make It Right, a nonprofit led by actor Brad Pitt. Make It Right plans to build homes in the Lower 9th Ward for 150 families, focusing on bringing back entire blocks rather than scattered houses.

When these blighted areas finally catch up to the restored grandeur of the tourist traps, New Orleans may finally be able to breathe easy once again.