Assembly offers opportunity to non-voters

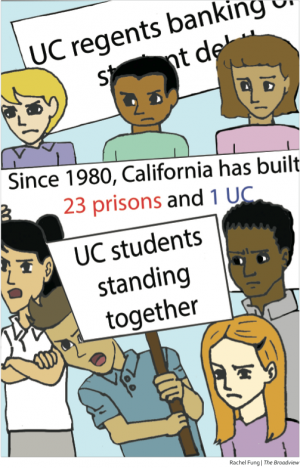

Lack of voting power leads minors to utilize First Amendment rights to assemble for voicing opinions, supporting causes.

September 28, 2017

Frustrated by outcomes of elections in which they had no say and policy changes which endanger their livelihoods, thousands of teenagers too young to vote have taken to the streets in recent weeks and months to let their voices be heard by exercising their First Amendment right to peaceable assembly.

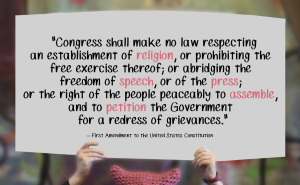

“Everybody has First Amendment rights — it doesn’t matter if you’re a citizen or not,” Rory Little, a law professor at UC Hastings, said. “It’s great to know your constitutional rights, but you need to be smart about how you exercise them.”

The exercise of the right to peaceable assembly may be one of the most complex of all, especially with heated situations that can easily develop in group settings, but can be one of the most effective ways for students and other underrepresented groups to share their opinions, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

“I went to the Science March in Washington, D.C. last spring,” senior Eden Schade said. “While it was more of a gathering of a group of people in support of a cause rather than a protest, it was amazing to see the number of people who decided to show up to support something they believed in. They could have assumed other people would go and stayed home, but they didn’t.”

Schade’s experience was not unique, but gatherings of frustrated and angry people can sometimes lead to violence, making it difficult to spread the idea or message the event was conceived around, according to Commander David Lazar, who leads the San Francisco Police Department’s Community Engagement Division.

“A group may say that its event will be peaceful while planning to commit acts of vandalism or violence, or a group may contain ‘splinter groups’ of violent protesters wanting to incite trouble. Law enforcement can be a conflict flashpoint,” Lazar said, “but we always try not to be.”

Because anyone can participate in a protest, regardless of their age or voter status, it is especially important to have a plan in place before attending an event, according to Lazar. Not drawing unnecessary attention through provocative clothing or signs, carrying identification at all times, having a contact outside of the area, and setting a time limit on participation can all make attending a demonstration a positive way to affect change.

“Be smart in terms of gauging the mood of the crowd in an effort to stay safe,” Lazar said. “If you ever feel unsafe, you can either leave the area and reassemble elsewhere or decide to call it a day.”

Senior Mary Crawford, who attended several protests this year, said that while going to the events probably did not change much in the way of policies, she felt better afterward.

“I’ve been to a few [protests], most notably the ones in the week after Trump’s election, one after the first repeal and replace of the [Affordable Care Act] and one at the airport after the travel ban in February,” Crawford said. “I went because I was disgusted with what I was seeing politically and felt a need to visibly and actively show dissent.”

Neither Schade nor Crawford ever felt unsafe at a protest, and both appreciated that the protest environment was more about being part of a group of people united under a cause they cared deeply about than anything else.

“The right to assemble lets us find strength in seeing others who share our goals, and can help show that there is a desire for change,” Crawford said. “Without the right to assembly, we would be significantly restricted in our ability to express our wants and needs.”