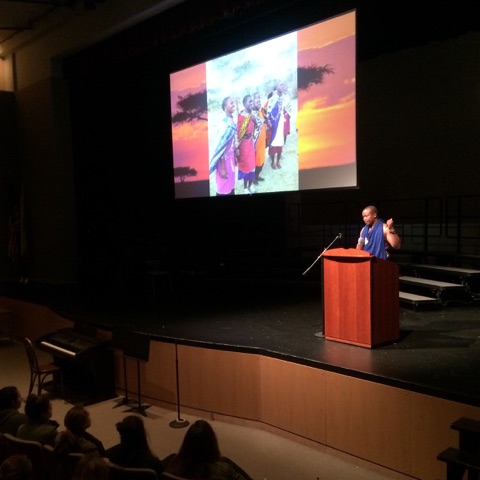

Maasai warrior informs about different cultures

Gerard Sayilel Murero, a Maasai villager from Kenya presented on women’s roles in Kenyan society.

December 12, 2015

Yesterday in the Syufy Theatre, Gerald Sayilel Murero, a Maasai warrior visited from southeastern Kenya to talk about a girl’s life in Kenya.

“I think it’s really cool, especially because you don’t know what it’s like until you’ve been there,” sophomore Francesca Petruzzelli said. “I can’t imagine walking to school and seeing an elephant.”

Murero’s stories of life in the bush gave students perspective on the differences between Kenya and America.

“Here you have buildings and vehicles; we have animals,” Murero said. “We fight lions nearly every day.”

Maasai culture teaches women household chores and beadwork from a very young age, and are commonly married off as teenagers. Their most important job is as a mother, according to Murero. Murero discovered the Maasai culture is drastically different from America when he arrived on Tuesday after riding an airplane for the first time.

“When a baby girl is born, she is considered a gift from God,” Murero said.

Murero is the managing director for the Kenyan Women and Children Foundation, a non-profit organization that works to educate women and children about wildlife conservation and the dangers of female genital mutilation, or female circumcision.

Female circumcision, commonly practiced in tribal cultures, happens when girls are 9-years-old as a rite of passage on their way to becoming a woman, according to French teacher Heather Wells, who studied female circumcision in college.

“It’s where a girl’s external genitalia are removed and the remaining skin is sewn together in smaller amounts, leaving a smaller opening,” Wells said.

Although female circumcision is a large part of traditional Maasai culture, it can have serious medical repercussions with reproductive health, causing more pain in intercourse and childbirth. Normally, it is not done in a hospital, by a doctor or using sterile instruments, according to Wells.

“The repercussions for women are both psychological and physical,” Wells said. “The experience in itself is highly traumatic.”

It is important for people in the U.S. to be aware about female circumcision, especially for those who want to pursue a career in medicine, according to Wells.

“Knowledge about it can make you as a doctor much more sympathetic to the physical and psychological repercussions,” Wells said, “creating the awareness of cultural differences and learning about it instead of just judging it.”

Along with preventing female circumcision, the KW&C Foundation strives to teach children about wildlife conservation and poaching, English, Swahili, mathematics, science and social sciences, according to Murero.

“The little kids can be four or 5-years-old, and they’re out with their herd of sheep or goats,” KW&C Foundation founder Linda VanderMarliere said. “A poacher can come to them and give them one dollar, and they’ll tell the poachers where the elephants are. So that’s why we need to educate the small children.”

The KW&C Foundation raises money through the marketing of jewelry made by Maasai women to donate school supplies and materials, such as desks, backpacks and stationary, according to VanderMarliere.

“The image that’s portrayed on American media is very different from the reality of the people,” VanderMarliere said. “They’re very kind, easy-going, gentle, gracious people. They embrace you when you come.”

Through their generosity and benevolence, VanderMarliere, an outsider, has become a part of the village. African wildlife and culture have always been her passion.

“Once you go there and you see this in person, it’s life-changing,” VanderMarliere said. “I wish everybody from here could go. It changes your outlook on life, and what’s really important.”