Workers often ‘pay the price’ for fast fashion

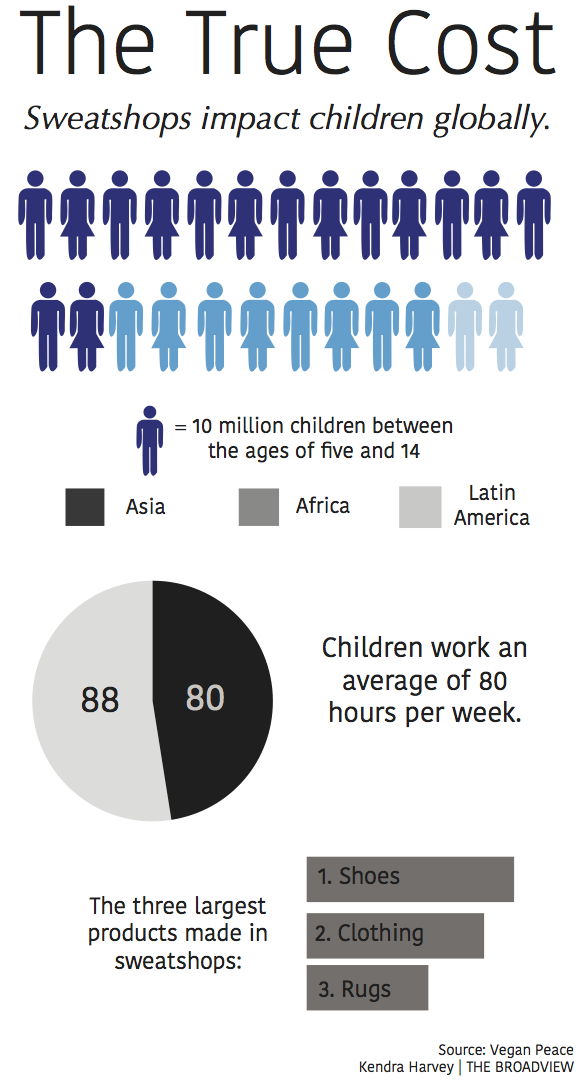

Low cost clothing is often sourced from sweatshops and child labor.

February 4, 2016

Colorful advertisements reading “Up to 75 percent off select items!” and “Fashion from $5!” cover buses, buildings and billboards in hopes of attracting potential customers, but behind the smiling models lies a world where people work for little more than slave wages and children sit behind sewing machines instead of school desks.

Offering cheap and trendy attire, “fast fashion” stores like Forever 21, H&M and Zara appeal to tweens, teens and adults alike, but although their offers may seem like a bang for a buck, the manufacturing practices of large, low-price clothing stores may not be such a dream come true for the people making the clothes.

“In terms of where my clothes come from and who I decide to support economically, it’s either companies who underpay their employees or companies who respect their workers,” junior Ana Paula Louie Grover, who is a member of the Fashion Club, said. “I take that into account now when I shop.”

As clothing prices decrease, the chance the company is turning to exploitiv e, outsourced manufacturing in order to maintain low prices increases.

e, outsourced manufacturing in order to maintain low prices increases.

“I just advise to avoid fast fashion,” Rachael Denny, who co-teaches a unit on oppression in the clothing industry in sophomore English and history, said. “Those we definitely know are coming from places where people are at least underpaid.”

The United States has the largest clothing industry in the world, with clothes accounting for 3.5 percent of an average American family’s yearly budget, but only a mere 2 percent of it is made in the United States, according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association.

By using foreign manufacturers, American retailers are able to produce more clothing for much less than if they were manufactured in the country, sacrificing normal pay and safe conditions for low prices. U.S. labor laws provide American workers with stable rights and regulation, but in developing countries where manufacturing is often targeted, companies are able to pay extremely low wages and are not burdened by employee healthcare and benefits.

“It depends on the type of garments that are being made, so for low-end garments it’s definitely cheaper to manufacture overseas,” Amy Hall, the Social Consciousness Director for Eileen Fisher, said. “But for higher quality garments, like ours or other high-end apparel, oftentimes the brand will go overseas for quality purposes. One prime example, at least in our case, is China. We actually get better quality garments from China than we can in any other place that we’ve tried, including the U.S., and it’s not cheaper for us.”

Although China is the global leader in clothing exports, many fast fashion companies source their manufacturing in Bangladesh due to lower wages and lack of regulation. Bangladesh has one of the lowest minimum wages in the industry at the U.S. equivalent of $68 per month, according to the International Labour Organization.

Many employees are forced to work shifts as long as 14 to 16 hours each day for seven days a week, bringing the total earnings to 15 cents an hour.

More developed and economically sound countries can provide a worker with more rights and pay than a worker in a poorer country, even if they are doing the same job.

“It’s aligned to the form of oppression inequality,” Denny said. “The idea that a girl in Bangladesh who is making the exact same T-shirt as a girl in Brazil, is making five to 10 times less. So they do the same work, but becauseof where they were born and where they are working, they are unequal.”

Unsafe working conditions in Bangladeshi factories came to the forefront in the Western world when the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people and injuring over 2,000, bringing to light the lack of safe conditions in many overseas garment factories. The incident led both American companies and the Bangladesh government to impose changes for inspection, workers’ rights and labor laws in factories.

Despite talk of reform in the clothing industry, workers continue to face physical and verbal abuse, forced overtime and failure to pay wages in a timely or complete manner that are often overlooked during inspections, according to Human Rights Watch.

“We have a team called Social Consciousness which has people attending to our environmental commitments, our human rights commitments and our commitments to our communities,” Hall said about Eileen Fisher’s corporate involvement. “We’ve done a lot of work around living wage, it is something that we find really difficult to tackle, and we’ve done a lot of studies and participated in a lot of multi-brand dialogue around how to really achieve this. We’re not aware of any other company that’s going to the measures that we’re going to right now to really start from within in terms of addressing living wage.”

Being the fifth largest specialty retailer in the United States, Forever 21 is reported to use questionable manufacturing practices to support its low prices, including the purchase of child-harvested cotton and the use of sweatshops, according to Business Insider.

Uzbekistan, the fourth largest exporter of cotton in the world, produces and harvests cotton with government-forced labor as well as child labor, according to Anti Slavery. While many other fast fashion retailers are boycotting Uzbek cotton, Forever 21 continues to use it for its clothing, according to the International Labor Rights Forum.

“If I do go into Forever 21 or those places, I usually just look around,” Louie Grover said. “You can definitely tell that they are the harbors of unjust manufacturing because of how cheap the prices are. So, I try to stay away from them and try to buy from different brands.”

Yet many teenage consumers continue to support what are commonly considered slave labor practices. Fifty-eight percent of respondents in a Broadview survey claimed to shop at Forever 21, even though 81 percent of them said that they would not support a clothing company that used child labor to manufacture their clothing. Seventy-one percent answered they would pay more for their clothing if it means the workers making the apparel would be paid a living wage, have safer working conditions and that the company would not use child labor.

“I think it depends on the person whether you buy less clothes for more money or more clothes for less money,” Louie Grover said. “I personally have the means to pay for higher quality and better manufactured clothing, I just think it depends on the people. But if I knew where my money was going and what I was supporting, I would pay more.”

Limiting one’s purchases and taking into account your true necessities can help break the chain of damaging manufacturing practices. By purchasing cheap, fast fashion clothing, the people manufacturing them will ultimately be the ones to pay the price, according to Hall.

“We’re all guilty of looking for a sale and looking for a good buy,” Hall said. “I think the question that we all have to ask ourselves is that the cheap price doesn’t come without another price somewhere else. Somebody has to pay for that.”

Forever 21 did not respond to requests for comment for this story.