College sexual misconduct ignored

Proposed legislative changes may further disadvantage victims

April 3, 2019

This story includes information about a sexual assault. The Broadview has chosen not to use the survivor’s name and has omitted certain details due to ongoing litigation.

What started out to be a friendly college get-together turned into a sexual assault for a female in her early 20s. After reporting the incident to her college, she says she felt victimized all over again.

With colleges’ increased concern about reputation, victimization may become the norm.

Colleges that receive federal funding are required to ensure that no discrimination on the basis of sex occurs in education programs and activities, including sexual assault and harassment, under Title IX of the Education Amendments Act, but new rules proposed by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos would change the way colleges comply to Title IX.

“If these proposed rules were to go into effect as they’re written, then schools would be allowed — and in many cases required — to ignore students who report sexual harassment,” Shiwali Patel, a Senior Counsel for Education at the National Women’s Law Center, said.

Approximately 20 percent of college women and 15 percent of college men are victims of forced sex during their time in college, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

Yet, 89 percent of universities reported zero incidents of rape in 2015, according to the American Association of University Women.

Current Title IX processes still raise concern about how colleges respond to complaints, which has led the Office for Civil Rights to have 305 open cases for colleges mishandling reports of sexual violence, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education.

“Universities are not expected to guarantee that no one will ever suffer sexual misconduct on their campus — that’s too much to expect,” Frank LoMonte, Volunteer Senior Legal Fellow at the Student Press Law Center, said. “What they are expected to do is to diligently follow up. When they get a complaint, they’re supposed to take it seriously and act with confidence, and if they don’t do that, that is when you start talking about a hostile environment.”

Under the proposed changes, schools would be required to presume that no harassment occurred until a determination is made.

“Our concern is that this would just exacerbate beratement that women and girls lie about sexual assault, or they’re reporting it because they want attention,” Patel said.

The woman in her early 20s, who claimed she was sexually assaulted by an acquaintance at her university and reported it to her school’s Title IX coordinator, experienced the process first-hand.

“It was awful,” the young woman said. “As I went through the Title IX process, I was very naive and trusted that they had my best interests and were really trying to prosecute him and get all the evidence they could.”

In September 2017, DeVos released a Q&A on Campus Sexual Misconduct to serve as interim guidance after rescinding the 2011 and 2014 guidance that included eliminating the 60-day time frame of investigations and giving schools the responsibility to collect the evidence.

The young woman said she believes her investigator was biased in favor of her assailant.

“The tone and the manner in which this lady spoke to me and asked her very skewed questions was unbelievable,” the young woman said. “She would purposely ask me questions that would confuse me and make me mess up my story.”

The young woman returned to her campus during a school break following the assault to be interviewed because of discrepancies between her statement and her assailant’s. When she received the final report, she was given time to read through it and submit a statement back.

“It was just filled with lies,” the young woman said. “I had to constantly relive my trauma not only from my own perspective but from the perspective of the guy who raped me.”

More than 90 percent of college sexual assaults are not reported at all and between 2 to 7 percent of reported sexual assault cases are false, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

Under the proposed rules, schools would only be obligated to investigate if victims reported their sexual harassment or assault to a Title IX Coordinator or “any official of the recipient who has authority to institute corrective measures on behalf of the recipient.”

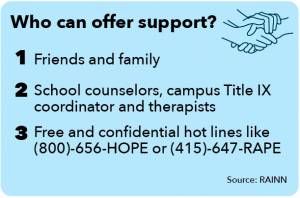

“When you think about who students opt to report to, it’s going to be someone who they trust,” Patel said. “If they’re a student athlete, it might be their coach; it might be their professor. It’s likely not going to be a dean or someone in a higher level who they might not know at all.”

The young woman said it took her several weeks to explicitly tell others she had been raped.

“Telling my parents was, and probably will be, one of the top three hardest things I have ever had to do in my life,” the young woman said. “I was holding back for that reason. I knew that the pain that this would evoke in my family and the suffering isn’t just consolidated to myself. I didn’t want to burden them with something so dire and unbelievably gruesome.”

Under DeVos’s proposed rules, the school would not be required to investigate the young woman’s case because it occurred off-campus.

“Schools would be required to ignore all Title IX complaints that occurred off-campus or outside of a school sponsored program, even if that student is forced to see their harasser or rapist on campus every day,” Patel said about the proposed rules.

Students living in on-campus dormitories and sorority houses are 1.4 times and 3 times, respectively, more likely to be raped than students living off-campus, according to a study published by the National Institute of Health.

“Just because the assault occurred off campus doesn’t mean that the trauma is any less severe,” Patel said. “Their education is still going to be impacted.”

A college woman is twice as likely to be sexually assaulted than robbed, as opposed to all women, who are robbed five times for every four sexual assaults, according to The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Current rules hold colleges to respond “reasonably” to complaints of sexual harassment, while DeVos’s proposed rules would require colleges to not act “deliberately indifferent” or “clearly unreasonable,” according to the National Women’s Law Center.

“For Betsy DeVos to think that this is a procedural process you can go through by completing steps one, two and three is just unbelievably naive, since this process is anything but ordinal,” the young woman said. “These revisions really are going to protect institutions further. When my dad read them he just started crying. It’s going to hurt the victims.”

The young woman said underreporting is one of the main issues with how colleges handle sexual assault.

“People are only focusing on the fact that sexual assault is happening on universities,” the young woman said. “Yes, that is the root of the problem. However, you have to tackle different barriers on the way. One of these barriers is the fact that every school is underreporting.”

LoMonte says that the vagueness in laws allows schools to interpret them broadly in their favor to keep sexual misconduct under wraps.

“Nobody wants to be known as a campus where a lot of sexual misconduct goes on,” LoMonte said. “That’s a blow to the college’s image. It really comes down to this fixation of promoting a favorable public image and not hurting donations.”

LoMonte says that statues like the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act need to be rewritten so they are not used to easily conceal sexual misconduct.

“It’s always easier to do your job without public scrutiny, but it’s not the way the law works,” LoMonte said. “The process should be as transparent as humanly possible because that’s the only way the public can have confidence that it works properly. The moment a college opens an investigation, they should be creating a version of the file that is the publicly disclosable.”

Knowledge that sexual assault investigations occur can cause other people to come forward, according to LoMonte.

“Once I found out that [my assailant] has done this to other girls, I thought, ‘This has to end somewhere,’” the young woman said. “I wish someone had done something before me, but the reality is, that did not happen. What matters is what I do from here on out.”

The Department of Education will review over 100,000 comments made by the public before making the ruling on DeVos’s proposal.

“It would not only further traumatize survivors who are trying to seek help, but would discourage many survivors and witnesses from the process,” Patel said. “I just think that they should not be moving forward with the proposed rules at all.”