Working around sexual harassment

Sexual misconduct remains a problem for women in the workplace.

The viral hashtag “#MeToo” has become a movement, as stories of dozens of women coming forward with allegations of sexual harassment continue to dominate headlines. But the issue of harassment goes beyond adults, affecting teenage girls who must decide how to react.

“Sexist remarks and catcalls are just constant,” a freshman, who wishes to be referred to as Jane, said. “On the street people have slapped my butt and whistled at me. I don’t know if they think they’re flirting, but it’s so disrespectful.”

Eighty-six percent of the female student body reported experiencing sexual harassment, with 93 percent experiencing catcalling, 69 percent experiencing gender harassment, 44 percent experiencing requests for sexual favors and 39 percent experiencing groping, according to an anonymous Broadview survey with 51 percent of student body responding.

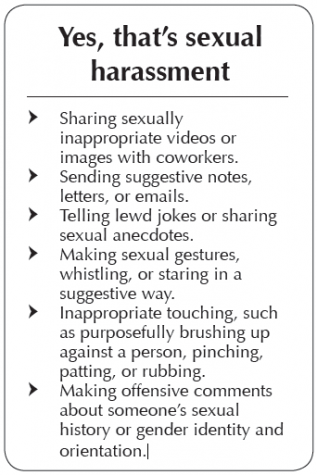

Sexual harassment includes unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Jill Sprague, an employment lawyer for CSAA Insurance Group, who leads company trainings on preventing sexual harassment, says that the frequent occurrences of quid pro quo harassment, the submission or rejection of a sexual act used as a basis for employment decisions, in the news surprises her.

“That stuff is happening a lot more than I ever thought, and I’ve been in the field for many years,” Sprague said. “It’s so widespread and blatant — all of these incidents coming out in the open has been really eye opening.”

Most of the harassment claims Sprague sees have to do with sexual gestures, suggestive looks, unwelcome physical contact or offensive jokes — harassment that creates a hostile work environment. Offensive comments about a person’s sex also constitute this kind of harassment, according to the EEOC.

Another student who wishes to be referred to as Mel says she experienced unwanted sexual advances, groping, and suggestive looks from multiple men at a paid summer position.

“It was very lecherous and uncomfortable,” Mel said as she pulled her knees to her chest. “One day this guy grabbed my buttocks and I thought, ‘I’m out. I can’t do this.’”

A friend of the source corroborated that Mel told her about the incident shortly after it happened, and the student left the position after feeling uncomfortable with the men.

“It opened my eyes to the reality of the world,” Mel said. “I’ve gone through all-girls education since kindergarten, and I obliviously thought something like that could never happen to me. It was a reality shock.”

Jane says she also received unwelcome touching and sexual advances while working at a swim club.

“I was 14 at the time and all my coworkers were over 18,” Jane said. “They knew I was underage, but one of the lifeguards would suggest for me to come over and hang at his place everyday. The week before I left, he would start to get [physically] touchy and it was not OK.”

Jane’s mother corroborated that her daughter experienced this harassment and informed her about how she was dealing with it at work.

Jane says she informed her boss and assistant manager that the man was making her uncomfortable. She also told two of her female coworkers, who told her they experienced similar harassment from the lifeguard, that he was making her uncomfortable.

“At the time I just thought, “Why do you think you have the right to do this to me?’” Jane said. “It’s degrading and sends a bad message to young women and teenage girls — they feel like they can’t do anything to stop it. I just get really angry at that.”

While Jane informed an authority figure, Mel did not tell her manager or confront her harassers because she was scared they would become aggressive.

“I’m 16 and there were all these men around me,” Mel said. “I couldn’t stand up for myself, so I just froze up and quit.”

When Sprague’s company receives a report of sexual harassment, it thoroughly investigates by talking to the victim and witnesses for any documents, such as emails, performance reviews or records of complaints, that could support or refute the claim and then makes a determination, she said. She says most companies follow a similar process.

“If we think that there was sexual harassment, then the company will act swiftly to discipline and possibly terminate the person who engaged in the conduct,” Sprague said.

An individual facing sexual harassment should tell the harasser that his actions are offensive and keep a record of all instances of the harassment, according to Equal Rights Advocates. The individual should then report the sexual harassment in writing to a supervisor, human resources department or other person who has the power to stop the harassment.

“I think it’s so important to tell someone what’s happening and let them know you’re uncomfortable and want to get out of the situation,” Jane said. “As long as somebody else understands that, you have more people supporting you and trying to send off whoever is sexually assaulting you.”

EDITORS’ NOTE ON THE USE OF ANONYMOUS SOURCES: The anonymous sources used in the above story, both of whom are minors, asked to remain so to protect themselves and maintain their privacy. In order to ensure The Broadview’s credibility as a publication, the Editorial Board discussed the implications of the use of anonymous sources. It corroborated each source’s account with her parents and friends, withwhom both sources discussed the incident shortly after it took place.