Cheap fashion enables abuse

Low-cost clothing promotes mistreatment.

March 15, 2016

As spring magazines highlight the season’s newest trends and hot styles, they often choose to focus on who’s wearing what while glossing over who’s making what.

Modern day slaves make up over 30 million people around the globe, much of which occurs throughout the production of apparel in the fashion industry, according to Not For Sale, a campaign dedicated to the protection of people from human trafficking and slavery. India is home to 14 million of the people tethered to present day slavery, and is also one of the largest clothing production exports in the world.

“It’s not as simple as just raising the price for an individual person,” Amy Hall, the Social Consciousness Director for Eileen Fisher, said in a phone interview. “I’ve heard from other brands that when the local community finds out that workers are earning more money, the local businesses raise their fees because they think they can get more money. In fact their net take home becomes no better than before the wage increased because their local cost is going up.”

Low wages, unlivable conditions and insufficient workers rights are only the tip of the iceberg as workers in leading fashion exports face both physical and emotional abuse as well as adverse discrimination in their working environment.

“I think it’s definitely important for us to touch on this in our club,” junior Charlotte Cobb, a co-founder of the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Fashion Club, said. “Students just need to know that there are people their ages being paid such a small amount for all the work they do. It’s completely inhumane and that’s what people need to understand.”

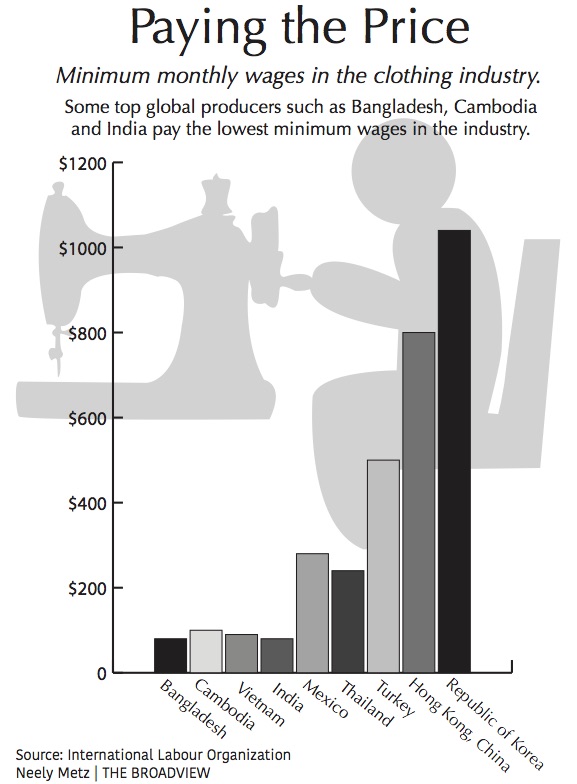

Generating $150 billion in illegal profits each year, 78 percent of modern slavery is labor related, according to the U.N. International Labor Organization.

Although the garment industry employs both males and females, 80 percent of industry workers are women. Employers prefer women over men due to cultural stereotypes that management can take advantage of in order to pay less, enforce longer hours and impose more abusive tendencies, according to Clean Clothes Campaign.

“It goes without saying that low wages in any country or community have a rippling effect to purchasing power, both for that family and the community,” Hall said. “In terms of women, there are studies that show when women become wage earners in families they earn more respect, which has a ripple effect outwards in terms of eliminating or reducing sexual harassment and abuse. Women then earn a higher status in the community because they have purchasing power and a certain value in the developing world.”

Women are more vulnerable to various forms of physical, emotional and sexual abuse, as their subordinate social standing makes it difficult to speak out about their mistreatment and exploitation. Although female employment has been said to reduce abusive agents, women continue to be demeaned, abused and limited in the garment industry and beyond.

Abuse targeted at garment workers runs rampant in many leading fashion exports, including Cambodia, where 90 percent of employees are women. Female workers in Cambodia’s garment sector face forced overtime, limited to no breaks and sexual abuse, while some workers are even underage children, according to research done by Human Rights Watch.

“The Responses to Oppression class, in the segment where we learned about mistreatment in the clothing industry, helped bring to light some of the issues in the industry,” Cobb said. “I think the maltreatment that workers are put through is one of the worst parts about the fashion industry.”

Although most abuse and mistreatment in fashion production takes place oceans away, some cases have been uncovered right in the United States. Forever 21 was called into court in 2010 by the U.S. Department of Labor for sweatshop-like conditions in their garment factories in Los Angeles, cited for evidence of wage, overtime and working hours violations among its suppliers.

This followed a similar case from 2001, in which workers in the LA factories complained of unfair labor practices and conditions, prompting Forever 21 to move the bulk of its production overseas. While most employees are paid per hour, workers in the LA factories are paid per garment made, allowing management to pay less than minimum wage and enforce more working hours.

“I’m more interested in clothing companies that practice proper production habits rather than mistreating their workers and just abusing the power they have as part of the clothing industry,” Cobb said. “I’ve still tried to find affordable things which can be difficult, but if you look hard enough you can find it. I think this also ties into the fact of looking at local companies and small boutiques in your neighborhood rather than big corporations which not only supports your local economy but you can almost always find places that don’t practice abusive production habits.”

Even though social and consumer awareness has increased, cash registers at fast fashion retailers, stores that sell trendy clothing for relatively cheap prices, continue to ring. In order to decrease the abuse occurring in factories employed by large fashion companies, customers need to consider the true cost of buying by limiting what they purchase, according to Hall.

“I’m actually going through a closet renovation, and I realized that what I wear in a week is probably all I need to have and all of this other clothing I could probably never see again,” Hall said.

“That’s really what we’re all facing right now,” Hall continued. “We should really think, ‘What is this going to do for my wardrobe and my lifestyle that I can’t already do now. How many wears will I get out of it?’ If it’s something that I’m only going to wear like once a year, I would say it’s not worth buying.”